ACL tears can be serious - so take them seriously

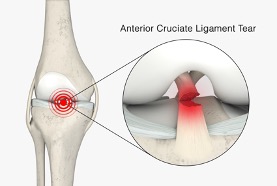

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a strong ligament in the middle of the knee that stops the tibia (the shin bone) from wobbling forwards, and, importantly it also helps provide rotational stability to the knee for cutting and pivoting type manoeuvres.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a strong ligament in the middle of the knee that stops the tibia (the shin bone) from wobbling forwards, and, importantly it also helps provide rotational stability to the knee for cutting and pivoting type manoeuvres.

How can you tell if it is an ACL injury?

The ACL is a common injury amongst footballers, skiers and netball players, particularly if one twists too hard on a bent knee: this then gives the classic ‘pop’ or ‘snap’ in the knee, normally with severe pain, and the knee gives way followed by the joint then swelling up significantly.

ACL - a serious knee injury

ACL tears occur frequently in athletes and those involved in contact sport, and an ACL tear can be a fairly devastating injury to a sportsperson, in terms of the time off sport that is then required.

ACL tears are common: if you even think ‘ACL’ then assume ACL… until proven otherwise!

If you think it's ACL, it probably is

If you think it's ACL, it probably is

If you even think ‘ACL?’, then you should consider your knee injury to be an ACL tear… until potentially (hopefully) proven otherwise – and this means that you’re going to need an MRI scan (preferably on a high-res 3-Tesla scanner, where the picture quality is as clear as possible).

Time and time again we hear the same old story of someone injuring their knee with them then going to their local A&E Department to wait hours and hours – if they’re lucky, then they might have an X-ray: but then they’re simply told that “there’s no fractures” and that “it’s just a soft tissue injury”. Be clear, this is an almost meaningless statement, and of almost no value at all! (Can you imagine if an A&E doctor or nurse told a Consultant Neurosurgeon: “don’t worry, there are no skull fractures: it’s just a ‘soft tissue’ injury”?!)

Experienced knee surgeons are needed for these sporting injuries

Sadly, sports injuries just don’t seem to be taken seriously within the NHS, and after being discharged from A&E most patients are simply told to go and see their GP. If they’re actually able to get hold of a GP… then most GPs seem to then simply send (fob) these poor patients off to a physio. There can then be another long wait, and for many patients nowadays ‘seeing a physio’ can be nothing more than them having a remote consultation either via video, if they’re ‘lucky’, or potentially simply by phone! Even if you do get to see a physio in person, are they a ‘good’ physio? Are they experienced in knee injuries? And even if they are, clinical examination only actually picks up about 80 to 90% of ACL tears, meaning that examination of the knee can miss 10 to 20% of tears! Let’s assume that you do end up seeing a good physio – well, what are they going to do?... Yes, they’re (hopefully) going to refer you for an MRI scan. Within the NHS this will most probably be an old low-res 1.5T scanner, and it could be weeks or even months before you actually get the scan.

The realities of getting good knee treatment

Once you’ve finally got your MRI scan on the NHS, then you’ve got to fight to be referred to a proper knee specialist, which means seeing a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon who specialises specifically in knees and sports injuries. And once you are finally on that list it could then be months before you end up being seen.

Not every ACL tear necessarily needs a surgical reconstruction; however, if you do actually need surgery the NHS waiting lists are currently at record levels and you may have to wait for literally years. Patients are being encouraged to shop around to get better waiting times. Then, if you do finally make it as far as actual surgery, you will need to establish who your surgeon is and what there qualifications, experience and performance outcomes are. The NHS gives you very little ability to pick and choose your individual surgeon, and do you really want to leave something as important as the long-term health of your knee down to ‘random’ luck, in terms of whether you’re seen by someone good, mediocre or potentially bad?

the longer you leave a wobbly unstable ACL-deficient knee, then the bigger the risk

Importantly, it’s been shown that the longer you leave a wobbly unstable ACL-deficient knee, then the bigger the risk is of the patient then developing meniscal cartilage tears in their knee, the lower the chance is of any meniscal tears actually be repairable, and also the higher the chance of the patient’s knee developing serious articular cartilage damage: all of which significantly adversely affect outcomes, the long-term health of the knee and the risk of future knee arthritis.

All patients have a right of choice of doctor and hospital.

Assessing your treatment options

The realities are that getting rapid and effective care through the NHS is increasingly challenging. If you have injured your knee and if you even suspect that you might have torn your ACL, then the only option may be to go private, and to pick and choose your knee surgeon carefully.

If I’m referred a patient with a suspected ACL tear, or if a patient self-refers to me with a history of a recent knee injury, then we will normally arrange for the patient to be referred for a 3T MRI scan, and the scan will be performed within literally just a few days. I can then see the patient in clinic ASAP afterwards (often even on the same day as the scan), and we will normally allocate the patient a 1-hour clinic slot, so that there’s plenty of time to go through things fully, in detail.

A high-res 3-Tesla MRI scanner (Pictured) is the gold-standard in knee imaging

A high-res 3-Tesla MRI scanner (Pictured) is the gold-standard in knee imaging

If a patient has torn their ACL, then the next thing to check is what other potential damage there might also be in or around the joint, such as meniscal cartilage tears, areas of articular cartilage damage or tears of some of the other ligaments around the knee too.

We then have to have a detailed and thorough discussion with the patient about exactly what they’ve done to their knee, what this means in terms of long-term prognosis, and what the potential options are, ranging from ‘conservative’ (non-surgical) management through to actual surgery, along with a discussion about what potential options there might be with the surgery (e.g. graft type choice for ACL reconstruction). These discussions include careful discussions about the potential associated risks of surgery, about the post-op rehab that will be required and about likely outcomes. This is why a 1-hour clinic slot can be so important, as there’s a lot to go through!

Informed choice for knee treatment

And then, after all of that, I then send my patients articles, papers and links to large volumes of further information for them to read, so that they’re as fully-informed as possible. My patients also get my direct e-mail address, so that they can then get back to me with any potential further questions that they might have.

Only then, once the patient is fully informed, is it then appropriate for them to even think about booking themselves in for any surgery, and if a patient does need surgery on their knee, then we’re normally able to offer them a slot for this within literally just a few weeks, depending on what’s most convenient for them.

Surgery for sports injuries

ACL reconstruction with a tendon graft: a highly-effective operation for stabilising a unstable ACL-deficient knee (see picture opposite).

ACL reconstruction with a tendon graft: a highly-effective operation for stabilising a unstable ACL-deficient knee (see picture opposite).

"This is how we run our service for sports injuries to the knee and for suspected ACL tears, this is the proper gold standard, and this is what all patients should have access to and how all patients should be treated".

ensuring that a patient is fully-informed about their knee injury and their potential options

A thorough knee consultation

A proper consultation requires adequate time, and shouldn’t be rushed. However, that’s then only just the start of the overall process of ensuring that a patient is fully-informed about their knee injury and their potential options.

REFERENCES

1. Treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Panther Symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group.

Diermeier et al.

Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy (2020) 28: 2390 – 2402

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00167-020-06012-6

2. The incidence of secondary pathology after anterior cruciate ligament rupture in 5086 patients requiring ligament reconstruction.

Sri-Ram et al.

The Bone and Joint Journal, 2013; 95-B(1): 59 – 64

https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/full/10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29636

3. Effect of Delayed Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction on Medial Compartment Cartilage and Meniscal Health

Everhart et al.

The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2019; 47(8): 1816 – 1824

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546519849695

4. Is Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Effective in Preventing Secondary Meniscal Tears and Osteoarthritis?

Sanders et al.

The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2016; 44 (7): 1699 – 1707

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546516634325