Following a year of trying for a baby 20% of women will remain unsuccessful. This article outlines the different tests undertaken for infertility as well as treatment options for couples seeking help conceiving.

Contents

- Ready to start a family?

- Age

- The process of conception

- From cleavage to implantation

- Measuring success

- Fertility investigations

- History

- Male investigations

- Female investigations

- Women are aware of subtle changes

- The final test

- Fixing any adhesions

- Organisation of fertility investigations

Ready to start a family?

It is a sad fact that most of us will spend our early years responsibly trying to avoid unwanted pregnancies and feel that as soon as we are ready to start a family all we have to do is to stop using contraception. Unfortunately, the reality is slightly more complicated than this. A couple with normal fertility only have a 20 to 30% chance of conceiving in any one cycle in which they have unprotected sex. After a year of trying around 80% of couples will have achieved a successful pregnancy and after two years of trying around 90% of women will be pregnant. This leaves around one in seven couples seeking medical help for delay in conception at some stage in their lives. So, if you are reading this after what has been for you a lengthy period of monthly cycles of expectation and disappointment, you are not alone. The good news is that most couples will be successful in having a family and success rates from assisted conception and other fertility treatments have never been higher than they are presently.

Age

The most important influence on fertility is the woman’s age.

Women are all born with their entire complement of eggs and from birth to menopause there is a continuous loss of eggs from the ovaries, which is entirely independent of whether or not women have periods, whether or not they are taking the oral contraceptive pill and whether or not they are actively trying to conceive. At birth there may be around 2 million eggs which drops to around a million at puberty and by menopause there are only a handful left.

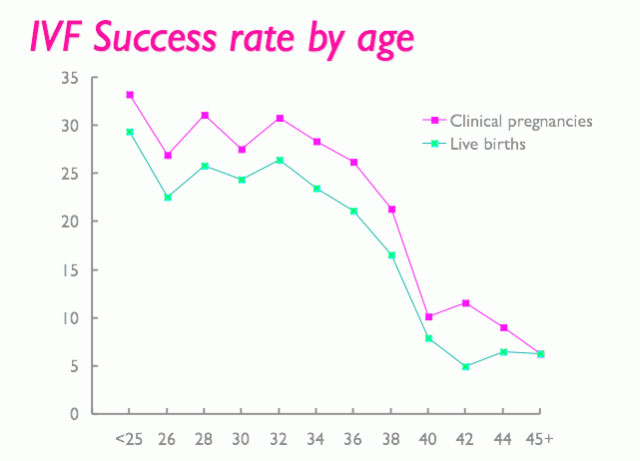

The graph in Figure 1 shows that there is a rapid drop in fertility from about 35-37 years of age. Whilst not all women will have met the man with whom they wish to have children by this age, if you are in a relationship and children are important to you, then the best advice is to strat trying as soon as you can, since your chances of success will only decrease with time.

The process of conception

Human reproduction is extremely wasteful. Each month around 250 eggs will progress from the resting stage of cell division and begin the maturation process. At the time of menstruation a variable number of these eggs will be contained in small fluid filled sacs a few millimetres in diameter, called antral follicles, which can be seen at ultrasound. A number of these follicles will increase in size under the influence of follicle stimulating hormone until they grow to around 12-14mm in diameter when one will become dominant and suppress the growth of all the rest. The dominant follicle will release its egg at ovulation, by which time it will be around 20mm in diameter, all the rest, including those which do not even produce visible follicles will be lost, to be replaced by the next cohort of developing eggs.

If this isn’t wasteful enough, the average human ejaculation will release hundreds of millions of sperms, of which only one will fertilise the egg that has been released at ovulation.

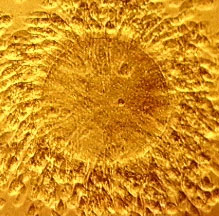

For this process of fertilisation to occur, the sperm have to “swim” from the vagina into the uterus via the cervix like so many microscopic tadpoles. From the uterus the sperm then swim into the Fallopian tube, which should have picked up the egg and gently waft it down the tube towards the cloud of sperm coming in the opposite direction. Although only one sperm will eventually achieve fertilisation the process requires hundreds of thousands of sperm to bind onto the mass of cumulus cells from the ovary that surround the egg. The sperm try to bury their way through these cumulus cells to reach the outer protecting membrane around the egg called the zona pellucida which allows only one sperm to penetrate it and fertilise the egg.

From cleavage to implantation

The fertilised egg then begins the process of cleavage and travels down the fallopian tube into the womb where the fertilised egg will hatch from the zona pellucida around 5 days after fertilisation and the process of implantation will then begin.

Measuring success

For implantation to occur successfully, the cells of the blastocyst signal the cells of the endometrium which line the uterus, stimulating rapid growth of the endometrium around the developing embryo and effectively embedding it in a protecting layer of endometrium. At the same time the embryo is releasing a hormone called human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) which tells the ovary to continue producing progesterone to support this very early pregnancy. Progesterone is an important hormone which supports the developing pregnancy until around 12 weeks of gestation. When fertilisation does not occur, the ovary stops producing progesterone at 14 days after ovulation and the fall in progesterone is the stimulus which causes the endometrium to be shed as a menstrual period. The presence of hCG in the urine is detectable from around the same time and is the marker used in urinary pregnancy tests. The concentration of hCG in the blood should double every two days in a normal, healthy pregnancy and sometimes we will measure this if we are worried about a pregnancy.

Fertility investigations

Basic fertility investigations aim to ensure that there is no breakdown of the exquisite and intricate process described above. In essence we need to know that the man is producing viable sperm, the woman is producing viable eggs and that it is possible that the eggs and sperm will meet. We also perform some blood tests to check on some of the hormone levels mentioned above.

History

The investigation process begins with a careful medical history being taken from both partners to see whether either have any conditions which may impact on the chances of conception, or whether there are any lifestyle or environmental factors of relevance. Previous surgery to the pelvis such as an appendicectomy or a past history of sexually transmitted infection may have caused damage to the fallopian tubes and mean that they are unable to pick up the egg once it is ovulated from the ovary. It is also important to ensure that there are no problems with sexual intercourse, and that it is occurring regularly and at the appropriate time of the cycle to maximise the chance of conception.

Male investigations

As far as the man is concerned the primary investigation is of course a semen analysis. The semen specimen should be examined within an hour of production and if possible examined at a WHO-accredited laboratory which has experience of treating subfertile couples. These laboratories are able to give a more accurate assessment of the sperm function and will be able to give some indication of treatment options that may be relevant to consider. If the semen analysis is abnormal then it may be necessary for some further blood tests to be performed on the man and for him to be examined and assessed by a specialist in male fertility, known as an andrologist. Further investigation may include a full examination and an ultrasound examination of the testicles and prostate. In certain cases an infection in the prostate gland known as prostatitis can significantly affect sperm function and it may be necessary to send the semen sample for microbiological assessment and culture to see whether any bacteria are grown in it.

Female investigations

From the woman’s perspective we normally commence investigations with a blood test on day 2 or 3 and a further blood test a week after ovulation to measure the progesterone level. This is done on day 21 of her cycle if she has a normal 28-day cycle, but if her cycle is longer than this then the second blood test should be done roughly one week before the anticipated date of menstruation.

Usually ovulation occurs 14 days after the period begins, but in some cases it may be rather later than this leading to a longer cycle. The luteal phase (from ovulation to menstruation) is almost always constant at 14 days and so a raised progesterone level in the mid luteal phase is a very good indication that ovulation is occurring.

Women are aware of subtle changes

There are also other subtle changes which some women are aware of, in terms of a change in the cervical mucus and a rise in the temperature in the second half of the cycle. Some women also experience pain at the time of ovulation.

The blood tests taken on day 2 or 3 of the cycle are designed to assist the function of the pituitary gland which is extremely important in regulating ovulation. The pituitary gland produces the Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinising Hormone (LH) which are responsible for the development of the follicle and the release of the egg respectively. A further hormone of ovarian origin called Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) has recently been advocated as a good indicator of ovarian reserve. The timing in the cycle of when this blood test is taken is not critical, but it is convenient for it to be done on day 2 of the cycle. Other blood tests may be indicated if any conditions of relevance to fertility are identified from the medical history.

The final test

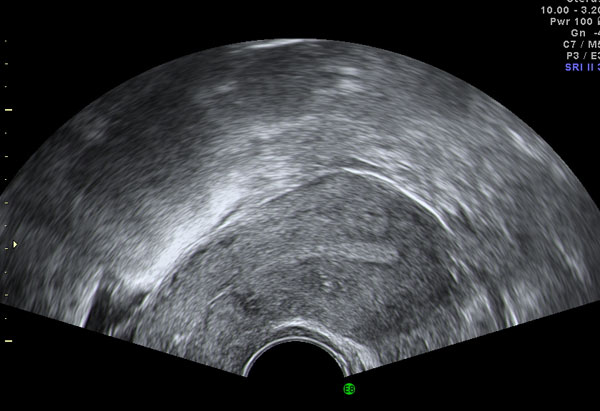

The final test of relevance is to confirm that the fallopian tubes are open and that the anatomy of the uterus and ovaries is normal. The first-line investigation for this is transvaginal ultrasound scan in which images of the uterus and ovaries can be constructed from a computer analysis of the effect of tissue on the reflection and absorption of very high frequency sound waves transmitted and received by a probe which is inserted into the vagina. The examination is quite painless and entirely safe and is used extensively during pregnancy to monitor the development and growth of the foetus.

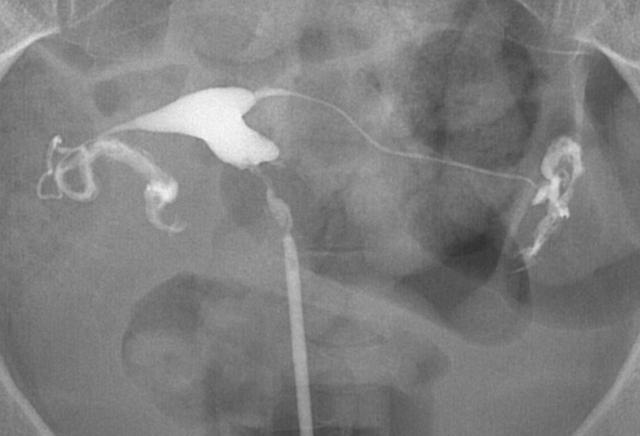

The patency of the fallopian tubes is assessed using x-ray visible contrast medium, after a scan has been performed, provided that there is nothing in the history to raise suspicions of external damage to the Fallopian tubes following infection or surgery. This examination is called a hysterosalpingogram or HSG. Contrast medium is injected with gentle pressure into the cervix, outlining the cavity of the uterus and spilling through the Fallopian tubes and into the pelvis in the normal examination.

There is some evidence that performing this examination can also flush the tubes through leading to a slightly higher rate of conception in the month or two following the examination.

Fixing any adhesions

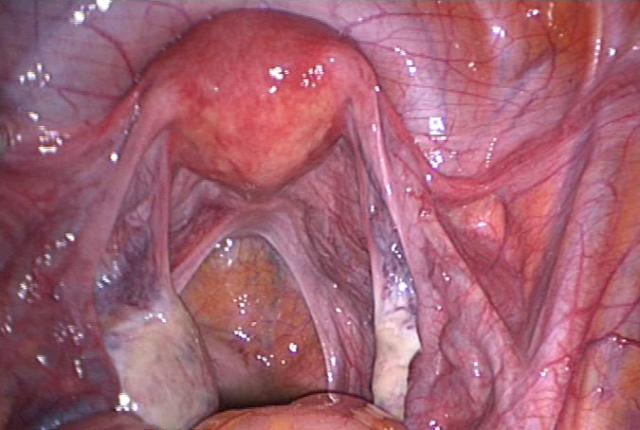

If there is a history of pelvic surgery or pelvic infection then it would be sensible to assess the fallopian tubes by a rather more invasive examination called a laparoscopy. This is performed under a general anaesthetic where carbon dioxide gas is introduced to the abdominal cavity through a small needle introduced to the navel. This carbon dioxide creates a potential space into which a telescope can be introduced with a video camera, which allows a very clear inspection of the pelvic organs. Appropriately trained surgeons can also often divide any adhesions which may be present and restore normal anatomy and function where possible.

Other important conditions which may be identified at either ultrasound scan or laparoscopy include uterine fibroids and endometriosis, both of which can affect fertility and both of which are likely to lead to an improvement in fertility if treated appropriately.

Organisation of fertility investigations

In the past, many of these conditions have been investigated in a disappointingly random and haphazard fashion at hospitals and it often takes a long time for a proper diagnosis to be established in the context of a general gynaecology clinic. More recently, fertility clinics are offering a one stop diagnostic service, where the blood tests can be performed at the appropriate time of the cycle and then on a single visit to the clinic the history can be taken, a semen analysis performed and an ultrasound scan and test of tubal patency also performed in order to establish a clear diagnosis.

It is also then possible to have a detailed consultation with a fertility specialist in which the various treatment options can be discussed and considered. The couple should then be given time to think about the options open to them before making a final decision. This arrangement is a much more efficient use of scarce medical resources and avoids lengthy delays and frequent clinic visits for couples who may have demanding professional and employment commitments.

Subsequent articles in this series will look at specific fertility treatments and what they involve for people who are experiencing a delay in conception.

For further information on the author of this article, Consultant Gynaecologist, Mr Adrian Lower, please click here.

An abbreviation for luteinising hormone, which is a hormone produced by the pituitary gland.

Full medical glossaryThe time of a woman’s life when her ovaries stop releasing an egg (ovum) on a monthly cycle, and her periods cease

Full medical glossary