Contents - Sports Injuries

- What makes the knee joint so susceptible to injury?

- Common injuries to the knee

- Knee injuries need expert assessment

- Rehabilitation for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury

- Knee surgery for ACL injury

- What does surgical reconstruction of the ACL involve?

- Benefits of ACL reconstruction

- ACL reconstruction in children

- Treatment options for a torn meniscus

- Repairing damaged tendons

Knee injuries are common in people who participate in sport at all levels. They cause pain, prevent training and lead to lowered fitness, sometimes requiring months of recovery. The impact on budding young professional athletes can be particularly severe. Prompt treatment, including rehabilitation and/or knee surgery, can prevent an early end to a career in sport and can lessen the risk of early degenerative knee disease.

What makes the knee joint so susceptible to injury?

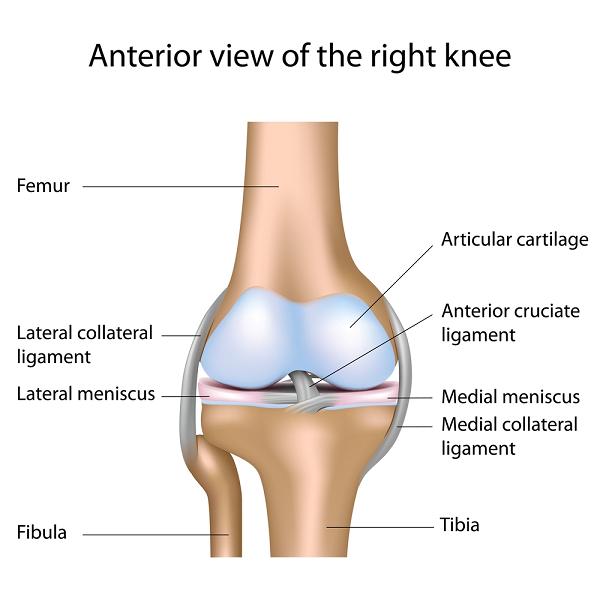

The knee joint is the body’s largest joint and it is a complex junction point. Three bones, the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone) and the patella make up the knee joint, together with several strong ligaments and tendons (click on image to enlarge). The joint allows a full range of movement and flexibility. The cartilage within the knee, the meniscus, and the articular cartilage provide an effective cushion, taking the impact of walking, running and jumping.

Being fit and active has many health benefits and is to be encouraged, but the downside is the extra potential for strain and wear and tear. Virtually all sports put pressure on the knee joint and the ligaments, tendons, menisci and articular cartilage within the joint can all sustain damage. This can happen in children and young adults who are active in sport, and it becomes even more likely as athletes get into their late 20s and beyond. Knee injuries sustained during sport can mean long breaks but may also lower the potential of a promising teenage athlete.

Common injuries to the knee

Athletes involved in sports that are considered 'high-risk' such as rugby, football, basketball and skiing, often injure the ligaments and cartilage in the knee:

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears - these often happen when moving fast and changing direction suddenly, or landing after a jump. ACL tears in children are becoming more common and now account for up to 3% of all ACL injuries reported.

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries - common in contact sports and caused by impact to the side of the knee.

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries - occur due to impact to the front of the knee or through falling awkwardly.

- Torn meniscus - tears in the menisci occur due to twisting the knee, sudden movements, or impact.

Knee injuries need expert assessment

It is unusual for a sports injury to be restricted to one ligament; knee injuries often involve the ACL, a meniscal tear, an MCL injury and even damage to the bone underlying the cartilage. Not all injuries need surgery; good results can be achieved with a well-designed rehabilitation and physiotherapy programme. Some combined injuries are still difficult to treat, with not enough evidence available on whether conservative treatment with rehabilitation is better or worse than knee surgery.

Expert assessment by a Consultant Surgeon specialising in knee injuries in sport is therefore essential. If surgery is necessary, it is better to use the most suitable technique and to operate sooner rather than later to prevent further joint damage.

Rehabilitation for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury

Physical rehabilitation should include proprioception (balance) training and exercises that specifically strengthen the hamstrings. Intensive rehabilitation should continue for 6–12 weeks. After that time, if there is no improvement or if the knee joint is still functionally unstable, then surgery is the follow up option.

Knee surgery for ACL injury

Various techniques are used to reconstruct the ACL by grafting tissue from a tendon obtained from the patient (autograft). The surgery is done arthroscopically – which involves a minimally invasive technique with small incisions, also known as keyhole surgery.

- Arthroscopic ligament reconstruction using a hamstring tendon graft: this is the currently recommended surgery for any ACL injury. Part of the hamstring tendon is used to reconstruct the anterior cruciate ligament. This method gives good results, has a relatively fast recovery and produces few problems with the hamstring tendon, which heals well.

- Arthroscopic ligament reconstruction using a patellar tendon graft: this surgery is often preferred for serious athletes but can cause later problems such as pain on kneeling, stiffness and even a fracture of the bone of the kneecap.

- Other grafting techniques: these include use of the quadriceps tendon from the same patient, or donated human grafts (allografts) of the tendons from various sites (hamstring, patella, and heel).

What does surgical reconstruction of the ACL involve?

The ultimate aim of the surgery is to restore full function and stability to the knee joint. Irrespective of the source of the tendon graft, the reconstruction surgery follows a similar path:

- The surgeon drills bone tunnels into the surface of the femur and tibia in the place where the original ACL was attached.

- The tendon graft is then fixed into place using screws, posts, washers or staples that can either be metal and permanent, or made from material that will be absorbed by the body after healing.

- Most surgeons use one strip of tendon tissue but the natural ACL is composed of a double bundle, so it is becoming more common to use two strips. This is a technically more demanding operation, and there is no firm evidence as yet that it produces better results.

Benefits of ACL reconstruction

Surgery reduces the risk that a patient with a torn ACL and an unstable knee joint will experience deterioration of the articular cartilage and the menisci in later life. People who have had a reconstruction using their own hamstring or patella tendon graft report being happy with the result, the way their knee works and their activity level 15 years later.

ACL reconstruction in children

This is more controversial than in teenagers and young adults but many surgeons recommend early surgery to prevent tears to the meniscus and degenerative changes to the knee if the joint remains unstable. Surgery needs to be carried out by an experienced Paediatric Surgeon, who must avoid damaging the bony growth plates that are still active at the ends of the femur and tibia.

Treatment options for a torn meniscus

Injured cartilage does not easily repair itself. The standard surgical technique is to remove the damaged meniscus using arthroscopy and then to encourage the formation of new cartilage to replace it. Minimally invasive surgery is recommended to remove the smallest amount of meniscus as possible as this produces less chance of damaging the joint and inducing early osteoarthritis.

After the meniscus is removed, the bone that lies directly under the cartilage is stimulated. Methods used include microfracture surgery, abrasion arthroplasty and Pridie drilling.

An alternative to physically damaging the underlying bone involves tissue engineering and transplantation but there is no evidence that these techniques produce better results:

- Autologous chondrocyte implantation - this involves taking bone cells (chondrocytes) from part of the articular cartilage that doesn’t bear any weight. These are implanted into the site of the damage cartilage, where the cells should produce new and functional load-bearing cartilage.

- Osteochondral autograft transplantation - the same bone cells are obtained but these are put into a gel-like matrix with growth factors before being implanted to the damage site.

Repairing damaged tendons

People who choose football, basketball or volleyball as their sport, or who opt for field events, skiing or tennis, often develop overuse injuries to their patellar tendon. These can be treated using physiotherapy but if this fails, surgery may be necessary.

Traditionally, open surgery has been used but this is being increasingly replaced by arthroscopic surgery to remove the damaged tendon. This is more effective, safer, and eventually leads to a higher level of recovery. Problems do arise when athletes return to their sport and training too early; the typical recovery time is nine months.