As winter approaches and the NHS launches its 2024-2025 vaccination campaign, British residents face familiar pressures to get their annual flu jab. Whilst protecting public health is a worthy goal, particularly for vulnerable populations, mounting evidence suggests we need a more nuanced understanding of flu vaccine effectiveness. This article examines the scientific evidence, policy decisions, and financial implications behind the UK's flu vaccination programme.

The reality of vaccine effectiveness

Comprehensive Cochrane Reviews, representing decades of research, reveal surprising findings about vaccine efficacy. Studies show that amongst healthy adults, seventy-one people need vaccination to prevent just one case of influenza. The numbers for children over two are marginally better, with approximately five needing vaccination to prevent one case, though this estimate carries significant uncertainty. Perhaps most concerning is that the most recent clinical trials for elderly populations are nearly two decades old. Furthermore, critical gaps exist in our understanding of how vaccines affect complications and disease transmission.

Understanding the numbers

Common statistics about flu impact often present a misleading picture. The standard American figure of 36,000 yearly deaths includes all types of pneumonia and respiratory deaths, creating an inflated perception of flu mortality. When examining actual death certificates, influenza deaths average around 1,000 yearly. Moreover, current surveillance systems fail to reliably track the relationship between influenza-like illness (ILI) and confirmed influenza cases, making it difficult to assess true vaccine impact.

Historical context

The evolution of flu vaccine policy reveals concerning patterns in public health decision-making. Since 1984, when American authorities first recommended annual healthcare worker vaccination, policies have expanded without proportional evidence to support them. A systematic examination of policy documents from major health organisations, including those from the WHO, UK, US, Germany, Australia, and Canada, consistently shows selective citation of evidence, misquotation of research, factual mistakes in reporting, inconsistent logic, and cherry-picking of favourable studies.

The policy-evidence gap

The disconnect between policy and evidence manifests in several troubling ways. The WHO, for instance, claimed a 70-85 percent reduction in serious complications for elderly vaccination, basing this sweeping statement on isolated studies. Policy makers frequently confuse vaccine efficiency and effectiveness, whilst evidence that doesn't support policy positions is often overlooked. Additionally, financial incentives appear to influence policy decisions more strongly than scientific evidence.

The 2024-2025 campaign structure

The NHS has established a staged rollout for its vaccination programme that begins with pregnant women and children on 1 September 2024. The main campaign launches for adult populations on 3 October, with a target completion date of 20 December 2024. The final cut-off for flu vaccinations extends to 31 March 2025, creating a particularly long window for vaccine administration.

Questions of timing

The campaign timing raises several significant concerns about vaccine effectiveness. The NHS acknowledges that vaccine effectiveness wanes over time, yet offers a six-month window for administration. This extended period raises questions about protection duration and optimal timing for vaccination. Furthermore, the assertion that children require earlier vaccination due to different circulation patterns lacks robust supporting evidence. The coordination with COVID-19 vaccine administration appears driven more by administrative convenience than clinical necessity, particularly given the absence of long-term safety studies on co-administration.

Understanding viral nature

The fundamental nature of influenza viruses presents challenges that policy makers seem reluctant to address. These viruses are inherently unstable, undergoing continuous shift and drift in their genetic makeup. Most infections resolve naturally and are benign, raising questions about the proportionality of the global machinery created to combat them. This biological reality undermines the effectiveness of any static approach to vaccination.

Research quality issues

Current evidence supporting vaccination programmes suffers from several critical problems. There is an over-reliance on poor-quality observational studies, whilst confounding factors substantially inflate perceived benefits. The limited number of randomised controlled trials available often show results that diverge significantly from policy claims, creating a troubling gap between evidence and practice.

Cost to the British public

Whilst the NHS provides vaccines 'free at point of service', the reality is more complex. British taxpayers ultimately fund the programme, including the financial incentives provided to healthcare providers for vaccine administration. The timing of the campaign directly affects payment structures, raising questions about whether administrative and financial considerations take precedence over clinical effectiveness. These resources might be better allocated to other health initiatives.

Global industry influence

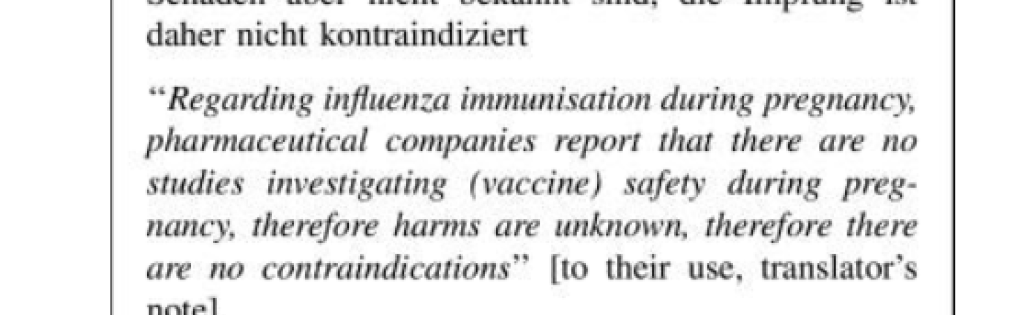

The pharmaceutical industry's role in shaping vaccination programmes warrants careful examination. Marketing efforts significantly influence public health messaging, whilst financial interests potentially shape research priorities. The cost-effectiveness of annual vaccination programmes remains questionable, particularly given their impact on healthcare resource allocation.

For UK residents

British residents should carefully consider their individual circumstances when deciding about flu vaccination. The minimal proven benefits for healthy adults, combined with the self-limiting nature of most flu infections, suggest that blanket vaccination may not be appropriate for everyone. The timing of vaccination within the campaign window and personal risk factors should inform individual decisions.

For healthcare providers

Medical professionals face a complex balance between policy directives and evidence-based practice. They must weigh individual patient needs against campaign targets whilst considering the ethical implications of vaccine co-administration. The disconnect between public health goals and scientific uncertainty requires careful navigation.

Conclusion

The evidence surrounding flu vaccines presents a complex picture that often contradicts official policy. Whilst vaccination may benefit specific high-risk groups, the blanket approach to population-wide vaccination lacks solid scientific support. British residents deserve transparent information about vaccine effectiveness to make informed decisions about their health.

As winter approaches and vaccination campaigns intensify, individuals should carefully consider their personal risk factors, the limited evidence for vaccine effectiveness, and the natural course of influenza infection. Alternative protective measures may merit equal consideration.

The gap between evidence and policy suggests we need a more nuanced, evidence-based approach to flu prevention. Until then, individuals must weigh the available evidence against public health messaging to make informed decisions about vaccination.

Additional comments / update to above article 6th November 2024

NB Full transcript and video via Camus on X

Robert F. Kennedy Jr requesting that the safety tests on vaccines are now done:

"I just want to make this clear. I don't want to take vaccines away from people. I don't want to impose my choices on the American public. If vaccines are working for you, you ought to be able to get them. And I'll make sure that happens. But people should have informed choice. So they should have good science that tells them the cost and the benefits of these products, particularly since they're being ordered to use them."

"76 million kids a year are required to use them. and they're healthy children. So it's the only medical product that's given to healthy people. You want a product like that to be extra solid, to make sure there's no risk, because you can take, you know, there's certain risks that you'll take if you're sick to get better. Of course. But if you're not sick, and you shouldn't be required to take a product unless it is iron-clad, unless you know what the... you know, what all the costs and benefits are."

"And the problem with vaccines is that they were originally introduced by the Public Health Service, which is one of the five military services. That's why there's a surgeon general. And the Public Health Service introduced them and pushed them as a national security defense against biological attacks on our country. So they wanted to make sure that if the Russians attacked us with anthrax with some other biological agent They could quickly formulate a vaccine and then deploy it to 220 million American civilians without regulatory impediments."

"A normal Medical product takes about eight years to get to market because it has to go through double-blind placebo controlled trials and you need to see long-term effects. There are many effects. On every medical product that have long diagnostic horizons long incubation periods. They didn't want to go through that because they said it's going to be a national emergency. So instead of calling it a medicine, we're going to call it a biologic and we're going to exempt biologics from pre-licensing safety studies."

"So there's no vaccine on that schedule, that 72 vaccines, that has ever gone through a pre-licensing safety study placebo-controlled trial against a real placebo. And that's wrong because that means that nobody knows what the risk profiles are on these products. And nobody can tell you whether that product is averting more problems than it's causing."

"And what I will do, you know, if I'm given this job in the White House, is I'll make sure that those studies get done, that there are people on the panels that approve these products that are not loaded with conflicts of interest. So it's real science. disinterested people and that doctors and patients and Americans know exactly what the costs and benefits of every vaccine are and can make a rational decision."