This article provides an overview of the symptoms, causes and diagnosis of uterine fibroids. This will be of help to any woman who thinks she may be suffering from this common condition.

Contents

- Introduction

- What are fibroids?

- How are fibroids categorised?

- Who gets fibroids?

- What controls the growth of fibroids?

- Can fibroids turn malignant (cancerous)?

- How do I know that I have fibroids?

- What symptoms can fibroids cause?

- What investigations should I have?

Introduction

Uterine fibroids, which are non-cancerous tumours, occur in up to 77% of women. Although they only cause symptoms in around a quarter of cases they remain the most common cause of hysterectomy before the menopause.

Hysterectomy rates are falling quickly in the United Kingdom as women seek alternatives to radical surgery. In many cases conservative measures can be offered to treat symptoms and avoid hysterectomy. In some cases, however, hysterectomy is still the best option for complete and timely resolution of what can be severely debilitating symptoms for some women.

Although fibroids are one of the most common conditions affecting women we know surprisingly little about them and their natural history. In this article I will outline the facts of which we are aware and dispel some of the myths about fibroids. I will also look at some of the important consequences of having fibroids, as well as discuss some the techniques doctors use to diagnose them.

In the subsequent articles I shall concentrate on the diagnosis and investigation of fibroids and the various options for treatment.These three articles, in combination, are useful for the lay-woman and her family to gain an understanding of the condition and the options for management. There is also an article in this series aimed at medical professionals and the well-informed lay person which goes more deeply into the research and technical aspects of the procedures.

What are fibroids?

Fibroids are benign (non-cancerous) tumours or growths affecting the uterus. The uterus is composed almost entirely of muscle fibres which are not capable of voluntary contraction, but nonetheless contract strongly during childbirth, expelling the baby through the birth canal.

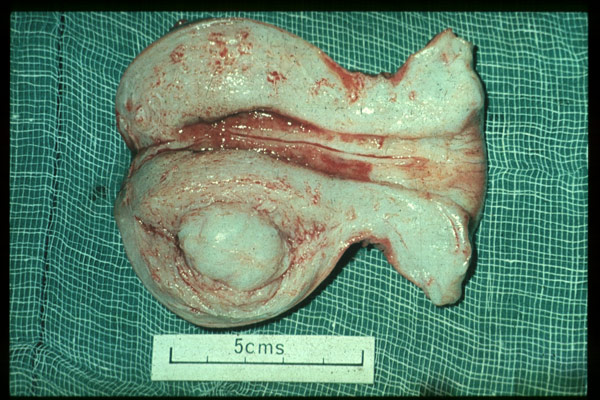

Fibroids are not composed of fibrous tissue at all, but each fibroid appears to grow by clonal replication of a single muscle cell. In other words, a single muscle cell starts to grow and replicate itself many thousands of times over, creating a firm muscular tumour with some associated new blood vessels and supporting tissues within it.

The normal controlling mechanisms restricting growth and replication of individual cells appear to be lost when a fibroid starts to grow. It is not clear why this happens, nor why some fibroids grow more rapidly than others and why some women have a greater tendency to develop fibroids than others.

How are fibroids categorised?

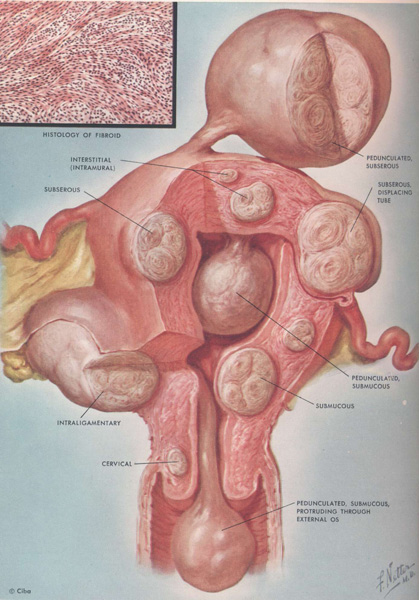

Fibroids are categorised according to their site in the uterus and their relation to the muscular wall of the uterus.

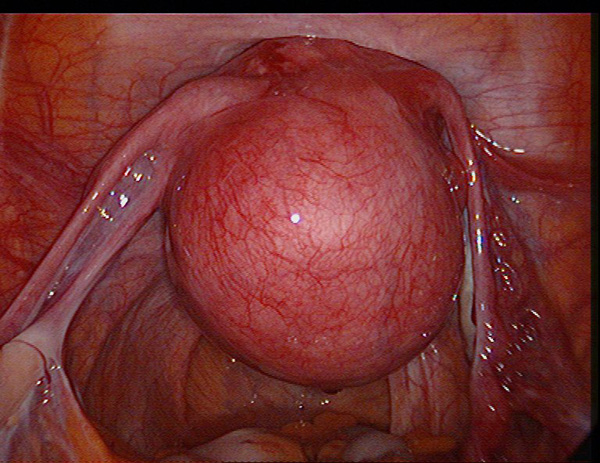

Fibroids that lie in a superficial position where the greater part of their diameter is outside the muscular wall of the uterus are termed subserous fibroids.

Some may even begin to separate away from the uterus on a stalk or pedicle containing the blood vessels which supply blood and nutrients to the fibroid. These are known as pedunculated fibroids. Rarely the fibroid can become attached to other structures in the abdomen such as the bowel or omentum (fatty tissue around the bowel) from which they may develop a blood supply. These pedicle attachments to the uterus can then sometimes become thinner and more tenuous and in some cases may even break off completely allowing the fibroid to become completely detached from the uterus and migrate elsewhere in the abdomen.

Fibroids that have the majority of their diameter within the muscle of the uterus or extend to both the internal and external surfaces of the uterus are called intramural fibroids. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between subserous and intramural fibroids, especially with very large fibroids when the outer muscular layer can be stretched very thinly over the surface of the fibroid.

Fibroids that extend predominantly over the internal (endometrial) surface of the uterus are known as submucous fibroids. Where less than 50% extends into the cavity of the uterus they are categorised as Type II, when more than 50% protrudes into the cavity they are called Type I and when they are completely inside the cavity or on an internal stalk they are called Type 0 submucous fibroids.

Who gets fibroids?

Studies have shown that African American women are up to three times more likely to develop fibroids than white, Hispanic or Asian Americans. We know that fibroids are also more common in black women elsewhere in the world, so there appears to be a genetic rather than environmental component determining whether or not women will develop fibroids.

It is not related to a single gene, but defects of the chromosomes of the cells making up fibroids can be demonstrated in over 50% of cases. Unfortunately we are not yet in a position to predict who will go on to develop fibroids on the basis of genetic testing.

What controls the growth of fibroids?

Fibroids are sensitive to the ovarian steroid hormones, oestrogen and progesterone. Progesterone seems to be the most import factor in causing the muscular cells to divide, increasing the number of cells in the fibroid, but oestrogen affects the size of the cells. This is why most fibroids tend to shrink when a woman reaches the menopause and oestrogen levels in the blood fall.

There are other signalling proteins in the body called growth factors which can also determine the rate at which fibroids (and other tissues) grow. Some are more plentiful in women who go on to develop fibroids. However we still know surprisingly little about why some women develop fibroids and why they grow more quickly in some women than in others.

Although many will claim otherwise, there is no convincing evidence that diet or avoidance of any particular dietary components has any effect on whether or not you will develop fibroids. Furthermore, if you do have fibroids there is no known dietary or drug treatment that will make them go away. Some drugs and complementary remedies may improve your symptoms and make it easier to manage with fibroids, but the fibroids, themselves, will not go away.

Can fibroids turn malignant (cancerous)?

In theory, malignant change in a fibroid is possible and has been used as an excuse for removing fibroids in the past. A study in Australia looking at the hospital records of patients at two major teaching hospitals over a 28 year period identified just 48 women with a malignant change in a uterine fibroid. That equates to less than one woman in a million in Australia developing a cancerous fibroid each year.

We believe the statistics are similar in this country. Therefore, routine removal of fibroids cannot be justified on the basis of avoiding cancer alone. However if a fibroid is growing very rapidly, the possibility of removal should be considered and some of the modern imaging techniques which can detect specific features suggestive of a potential malignancy should be employed.

How do I know that I have fibroids?

Fibroids are so common that they develop in up to 77% of women. Many women do not know that they have them as probably only a quarter of fibroids will cause symptoms. There is no need to worry about fibroids unless they start to cause symptoms. If you do develop some of the symptoms listed below you should see your doctor who will examine you and organise an ultrasound scan in the first instance. Or, your doctor may refer you directly to a gynaecologist who can perform a scan for you and discuss what treatment, if any, is required.

What symptoms can fibroids cause?

Fibroids can cause a variety of symptoms. Often the onset is insidious, as they tend to grow slowly and you may not notice that there has been any deterioration until they are quite large.

Perhaps the most common symptom is heavy and painful menstruation, typically caused by submucous and intramural fibroids. Sometimes there are cramps as the uterus tries to expel the fibroid with painful contractions. Larger subserous fibroids tend to cause local pressure symptoms leading to pain when opening the bowels or passing urine. The sheer size of these fibroids can cause abdominal distension and bloating. In addition, pressure on the bladder can lead to increased frequency of passing urine.

Submucous and intramural fibroids can cause a delay in conception and increased risk of miscarriage. All fibroids can cause complications during pregnancy, such as placental separation (abruption), premature delivery, obstructed labour and painful degeneration of the fibroid.

What investigations should I have?

The first line investigation is a careful history to determine what problems or potential problems you have encountered to help to guide in management. An internal examination will usually demonstrate enlargement of the uterus. Confirmation of the size, site and number of fibroids can usually be obtained by performing an ultrasound scan.

If your periods have been heavy it is sensible to perform a full blood count to check your haemoglobin in case you have become anaemic. It is also sensible to perform a blood coagulation screen, particularly if surgery is under consideration, in case you have a tendency to bleed excessively or your blood has a tendency to clot more strongly putting you at risk of thrombosis.

Sometimes an ultrasound scan is not conclusive, especially if your fibroids are very large, or if the endometrium is not distinct. A magnetic resonance (MR) scan is very useful in these cases.

Based on the results of these basic investigations, an experienced gynaecologist can help you to decide which is the right treatment option for you. We shall explore these options and look at methods of diagnosis more fully in the next articles.

If you would like a private appointment to see Mr Lower complete our simple online form.

For further information on the author of this article, Consultant Gynaecologist, Mr Adrian Lower, please click here.

The time of a woman’s life when her ovaries stop releasing an egg (ovum) on a monthly cycle, and her periods cease

Full medical glossary