Researchers at the Technical University of Munich have discovered that problems with tiny structures inside our cells, called mitochondria, may trigger Crohn's disease by disrupting the balance of bacteria in our gut.

What the study found

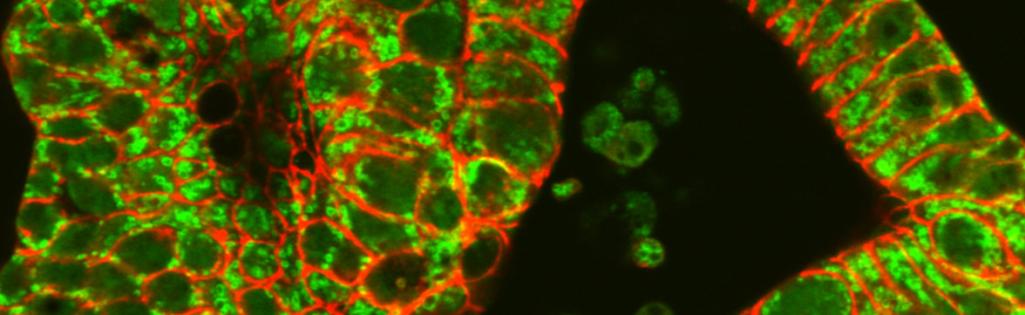

Scientists have known for some time that people with Crohn's disease have unusual patterns of gut bacteria (known as the microbiome). These changes in the gut's bacterial community have been linked to inflammation, but until now, researchers didn't understand what caused these changes in the first place. This new research suggests that when mitochondria - the 'power plants' of our cells - don't work properly, they not only damage the gut lining but also significantly alter the balance of bacteria living in our intestines.

Why this matters for patients

Crohn's disease can cause several distressing symptoms. Patients often experience chronic diarrhoea, along with significant abdominal pain. Many also suffer from fever during disease flare-ups. These symptoms are believed to be partly caused by an unhealthy balance of gut bacteria, which can trigger inflammation.

Currently, doctors can only treat the symptoms of Crohn's disease using anti-inflammatory medicines. However, this research opens up exciting possibilities for new treatments that could target both the faulty mitochondria and the resulting imbalance in gut bacteria.

How the research was conducted

The research team, led by Professor Dirk Haller, studied mice with faulty mitochondria. Their investigation revealed that these mice developed damage to their gut lining similar to that seen in Crohn's disease patients. Importantly, they also found that the community of bacteria living in the mice's intestines changed dramatically when the mitochondria weren't working properly. These changes in gut bacteria closely matched the patterns seen in human Crohn's disease patients.

What this could mean for future treatments

Professor Haller suggests that new medicines which could repair faulty mitochondria might be key to better treatments for Crohn's disease. By fixing the cellular 'power plants', we might be able to restore a healthy balance of gut bacteria. Rather than just dealing with inflammation after it happens, these treatments could help prevent the damage and bacterial imbalance that trigger inflammation in the first place.

What happens next?

While this research is promising, it's important to note that it's still in early stages. The next step would be to develop and test treatments that can target mitochondria effectively in patients with Crohn's disease. Researchers will also need to better understand how improving mitochondrial function might help restore a healthy gut microbiome.

This article is based on research conducted at the Technical University of Munich under the direction of Professor Dirk Haller, Chair of Nutrition and Immunology and Director of the Institute for Food and Health.