Latest Options for Treating Uterine Fibroids - Contents

- Introduction to management options for treating fibroids

- Management Options for Uterine Fibroids

- What about the ovaries?

- Conclusion

Introduction

Often referred to as uterine myomas, fibromas or leiomyomas, fibroids are benign (non-cancerous) growths that develop in or around the womb. They consist of muscle cells and fibrous connective tissue.

Fibroids are a very common and according to studies up to 77% of women will develop fibroids during their reproductive years. However, many women are unaware that they have fibroids because they simply don’t experience any symptoms. Further to this, only 1 in 3 fibroids are large enough to be detected by a health care professional during an examination.

Diagnosis

Fibroids can be accurately diagnosed with:

- Transvaginal ultrasound

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- or SIS (Saline Infusion Sonohysterography) This investigation uses saline solution to distend the uterine cavity and accurately detect the presence of submucosal fibroids.

- Hysteroscopy: A small telescope is inserted through the vagina. It provides a visual examination of the cervical canal and the uterus and is the gold standard investigation for the diagnosis (and treatment) of submucosal fibroids. In the vast majority of cases it can be performed without anaesthetic.

There are three different types of fibroids:

- Intramural fibroids – They develop in the muscle of the womb and depending on their size they can distort the shape of the uterus and cause heavy periods, pain and pressure.

- Subserosal fibroids – they originate in the muscle wall but protrude outside the womb into the pelvis and the abdomen.

- Submucosal fibroids – they grow into the inner cavity of the womb and they are more likely to cause irregular and heavy bleeding or difficulties when trying to conceive.

Management Options

A number of options exist to treat uterine fibroids. The appropriate treatment will depend on the size, site and number of fibroids, the symptoms they are causing, your age and whether or not you have had children in the past or plan to have them in the near or distant future, your desire to conserve your uterus or otherwise and how much time you are able to spare for recuperation or convalescence.

The treatment options include:

- Medical Management

- Hysteroscopic Resection

- Laparoscopic Myomectomy

- Uterine Artery Embolisation

- Open Myomectomy

- Outpatient Fibroid Treatment

- Hysterectomy

Medical Management

Medical treatments for fibroids work by regulating the hormones that are involved in the menstrual cycle and they reduce the size of fibroids rather than preventing or eliminating them. Drugs and hormones can be used to control the symptoms of fibroids, either to delay further treatment, or to try to allow women to get through to the menopause when fibroids tend to shrink naturally. However, if oestrogen replacement hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is used during the menopause this will cause the fibroids to grow again.

The effect of drugs that are used to shrink fibroids is usually only temporary and any reduction in size will be negated once the drugs are stopped. Sometimes it is helpful to take a drug to shrink fibroids prior to surgery to make it easier to complete the surgery. There is also some evidence to suggest that this may also reduce blood loss during surgery.

The types of drugs that are most commonly used to reduce the heaviness of periods are synthetic progesterone-like hormones called progestogens. These can be taken as tablets (Norethisterone) or in the form of a levo-norgestrel releasing intra-uterine system known as a Mirena.

The side effects of these drugs are usually well tolerated and include fluid retention and sometimes bloating. The daily dose released by the intra-uterine system is much less than that of tablets so the side-effects are usually less as the IUS is active at the site of absorption.

If heavy and clotty periods are the most troublesome symptom a drug called Tranexamic acid may be useful in reducing blood loss at the time of menstruation. This should not be used for more than a few days at a time.

Because fibroids are sensitive to oestrogen, drugs that reduce circulating oestrogen levels can reduce the size of fibroids. The most commonly used of these drugs are Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) given by daily or monthly injection. However, these drugs can cause menopausal-like side effects, including hot flushes, tiredness and emotional swings. Although the side-effects are reversible and stop once the drug is discontinued they do mean that the use of these drugs are restricted but they are particularly useful before hysteroscopic resection (see below).

Hysteroscopic resection

This procedure is suitable for smaller submucous fibroids of up to 4 or 5 cm in diameter and which lie either adjacent to or extend directly into the uterine cavity. Fibroids such as these, even if they are only 1 or 2cm in diameter are most likely to adversely affect fertility and cause distressing menstrual symptoms.

Sometimes it is helpful for a woman to take a hormone drug for a month or so prior to this type of surgery to reduce the size and blood flow to the fibroid, thus facilitating surgery. This hormone is called a Gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) and is given either by monthly or daily injection or taken by nasal inhalation. It achieves its effect by causing a reduction in your blood oestrogen levels

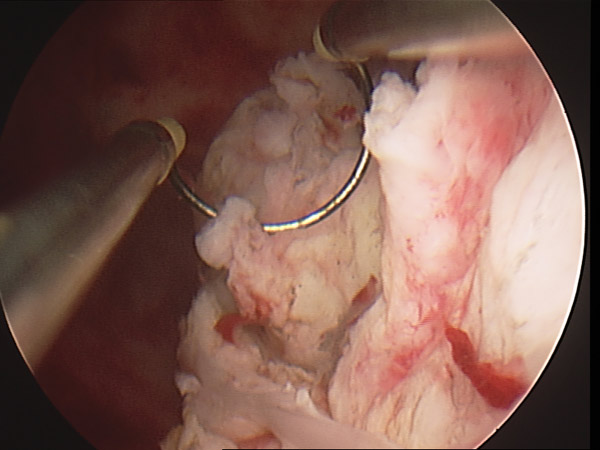

The procedure is usually performed under general anaesthesia, when a 4mm in diameter telescope is introduced into the uterine cavity with a wire loop attachment which heats up by the application of high frequency electrical energy to enable the surgeon to cut the fibroid into a series of strips of about 5mm in thickness (Fig 2).

The view within the uterus is maintained by a clear fluid called glycine, which distends the uterine cavity and does not conduct electricity. Unfortunately this fluid can cause some unpleasant side-effects if too much is absorbed into the blood stream through the rather vascular bed of the fibroid. For this reason, particularly with larger, deep-seated fibroids we sometimes have to do a two-stage procedure if the volume of fluid absorbed becomes too great. Luckily hysteroscopic resection of fibroids is generally very well tolerated and is usually a day-case procedure. There is not usually too much post-operative pain, but bleeding can often continue for up to two weeks after surgery.

This short video with commentary shows a small fibroid being resected.

--video1--

Laparoscopic Myomectomy

This procedure is more suitable for subserous or intramural fibroids up to about 10cm in diameter. Subserous fibroids are unlikely to adversely affect fertility and often don’t cause too much in the way of menstrual symptoms. They can cause pain, particularly if they are pedunculated, which can sometimes twist, cutting off the blood supply to the fibroid. Subserous fibroids can also cause pain and other complications during pregnancy and can grow extremely large surprisingly quickly. With laparoscopic surgery they can easily be dealt with before they get too large. The complications with this type of fibroid are minimal and often they will not need too much suturing which is the difficult part of the laparoscopic procedure.

Intramural fibroids are more difficult to treat and also often cause delay in conception and fibroids of only 3cm in diameter will reduce the chance of conception by 50%. They represent some of the most challenging surgical problems for laparoscopic surgeons. In such cases careful preoperative assessment is vital so that the surgical incision in the uterus can be planned appropriately.

In laparoscopic myomectomy a telescope with a video camera attached is introduced through a 10mm incision in the navel and 3 further ports or trocars are introduced through small incisions in the abdominal wall to allow instruments to pass through to perform the surgery under video surveillance. A well-equipped theatre and highly professional support staff are essential to success. The advantage of laparoscopic surgery is that the whole theatre team can observe the procedure and anticipate equipment that may be required. Fig 3 shows the abdominal incisions used for laparoscopic myomectomy.

For more superficial or pedunculated fibroids the stalk is coagulated with electrical energy and then cut, releasing the fibroid from the uterus.

This video shows the initial steps of a laparoscopic myomectomy for a pedunculated fibroid.

--video2--

For intramural fibroids the muscular wall of the uterus is incised using either a hook or scissors with high frequency electric current which cauterises small blood vessels, reducing bleeding. The fibroid is then carefully stripped away from the normal muscle of the uterus. The defect is then repaired using dissolvable sutures to obliterate the dead space left by removing the fibroid and repair the outer, serosal surface of the uterus. The suturing is the difficult part of the procedure. Very few surgeons in this country regularly perform laparoscopic suturing and this is the main obstacle to widespread uptake of the procedure. Most surgeons do not achieve this level of hand-eye coordination until they have been performing laparoscopic surgery for many years. The difficulty lies in performing complex movements in a confined space using both the dominant and non-dominant hand on a two dimensional video monitor. We are currently assessing the effectiveness of a new knotless suturing technique, which we hope will considerably simplify the process, making it more accessible to a greater number of patients.

The final problem is to remove the fibroids from the abdominal cavity. This is done using a morcelator which is introduced through one of the lower abdominal port sites. The morcellator can be seen in Fig 4. It consists of a tube of 12 mm in diameter with a rotating cylindrical knife blade inside which removes the fibroid tissue cutting it into long sausages of tissue. It is essential that the blade is kept well in view throughout the procedure.

The video shows the morcellator being used to remove a large fibroid from the peritoneal cavity.

--video3--

Myomectomy is recognised as one of the operations most likely to cause surgical adhesions and careful attention must be paid to adhesion prevention. At The London Fibroid Clinic we usually use a solution of Icodextrin, but there are a number of other products which act as a barrier between the healing tissues.

Post-operative recovery is rapid, and most patients leave hospital less than 24 hours after surgery. The majority can return to work within two weeks, although it is important that patients realise that they have had major surgery and they should allow adequate time for rest and recuperation.

The complication rate following laparoscopic myomectomy has been shown to be lower than open surgery in terms of the need for blood transfusion, infection and wound infection. Some authorities have expressed concern that the repair of the myometrium may be less strong than after open surgery and so there may be a higher rate of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies. The limited evidence available on this aspect is conflicting. Further studies are required. For the time-being we recommend a formal trial of scar, as we would following an open myomectomy, with intrauterine pressure monitoring in a specialist obstetric unit or an elective Caesarean section.

The video shows a laparoscopic myomectomy being performed.

--video4--

Uterine Artery Embolisation (UAE)

Also known as Uterine Fibroid Embolisation, Uterine Artery Embolisation (UAE) is a procedure in which the major blood vessels supplying the uterus and fibroids are selectively blocked, under x-ray control, using fine particles of glue. Loss of the blood supply causes death of the fibroid tissue, which is then reabsorbed by the body. Using this technique we can usually achieve a 60% reduction in size of fibroids and often complete resolution of symptoms.

UAE is used for cases where there are multiple fibroids and particularly where it may be difficult to find any normal tissue to repair after the fibroids have been removed. It is also useful for larger submucous fibroids, too large for hysteroscopic resection, and in these cases we can often achieve complete elimination of the fibroid rather than shrinkage as these fibroids will often slough off the internal surface of the uterus and be passed out of the uterus by contractions of the uterine muscle.

Access to the blood vessels supplying the uterus is gained through a small incision in the groin only 1cm in length. Under x-ray control, the blood vessels supplying the fibroids are identified with radiographic contrast medium. The patient is lightly sedated during the procedure, which takes between 30 to 60 minutes, and is not unduly painful. Once the vessels have been blocked off the tissue is starved of oxygen and dies. This can be rather painful, and is exactly analogous to the pain experienced in a heart attack where the heart muscle is starved of oxygen. Patients usually need to stay in hospital for a couple of days on intravenous pain control. On discharge from hospital they will still require quite heavy doses of oral pain medication for a couple of weeks and most will not feel like working during this time.

The fibroids achieve maximum shrinkage between three and nine months after embolisation. Many doctors are concerned about the long-term effects of embolisation on the blood supply of the uterus and the impact this may have on future pregnancies. The good news is that the normal muscle of the uterus soon develops a new blood supply and our research has shown that amongst those women who do conceive following embolisation, the obstetric complications are no different from the background poplulation.

Unfortunately, what we do not yet know is how many women undergoing embolisation, who want to conceive, have been successful in doing so. For this reason we have some reservations in offering embolisation to women who are actively trying to conceive, as first line treatment, although in certain circumstances where fibroids are particularly numerous or with very large submucous fibroids UAE may still be the best option for treatment of women seeking to conceive. Most authorities agree that embolisation is better suited for women whose families are complete, who wish for relief of their symptoms but want to avoid major surgery. Click on the link to read an article on Uterine Embolisation.

Open Myomectomy

Open myomectomy is the accepted method of managing fibroids and is practised by most Consultant Gynaecological surgeons. Access to the uterus and fibroids is through a standard surgical incision on the lower abdomen. Usually it will be a transverse incision, like a Caesarean section scar, but for larger fibroids extending above the navel, the incision may need to be vertical, in the midline to improve access. Fig 6 shows a lower midline incision for very large fibroids.

The main risk of an open myomectomy is of bleeding from the uterus. The larger the fibroid, the greater the risk of haemorrhage. Where multiple fibroids are present, and a proportion are subserous, we sometimes offer embolisation immediately prior to surgery in order to decrease the amount of blood loss. The surgeon can then operate in an almost bloodless field and ensure that the muscle of the uterus is carefully repaired. It is likely that the recurrence rate of fibroids will be less after concurrent embolisation, since any small fibroids not identified and removed at the initial surgical procedure will be killed.

Sometimes we will use a GNRH-analogue for a month or two before surgery. This lowers the blood oestrogen level, which tends to shrink the fibroids and making them less vascular. GnRH-analogue treatment can be used for up to six months, to delay surgery for personal or professional reasons, and during this time the periods will stop. Unfortunately the drug induces menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes and tiredness. It also causes loss of bone density and can lead to osteoporosis if taken for more than six months. These symptoms can be limited to some extent by the use of the oral contraceptive pill or a low dose of hormone replacement therapy.

At surgery the fibroids are identified and stripped away from the normal muscle of the uterus and the dead space left behind is obliterated using dissolvable sutures. Careful surgical technique must be employed to ensure a good repair of the serosa, or outer surface of the uterus, to minimise the chance of adhesions being formed. The use of fine, monofilament sutures is also important in this respect.

Open myomectomy is recognised as being extremely likely to cause post-operative adhesions and most gynaecologists now accept the need for adhesion prevention strategies. We routinely use a solution of Icodextrin to float the tissue apart during the healing process. Various gels, sprays and meshes have also been developed to assist with this important problem.

Care must also be taken not to damage the endometrium, the thin glandular tissue lining the uterus. Although the superficial part of the endometrium is shed each month when menstruation occurs, if the deep glands are lost dense intrauterine adhesions will result leading to a condition called Asherman’s Syndrome. This can be extremely difficult to treat and cause miscarriages and infertility.

Outpatient Fibroid Treatment

Ulipristal acetate (Esmya) is a new medical treatment of fibroids. Women over 18 years of age are given 1 tablet a day for up to 3 months. The fibroids shrink, the bleeding stops and the symptoms improve. Esmya was previously only licensed for the pre-operative use in the treatment of fibroids but can be now used intermittently to treat moderate to severe symptoms of fibroids in women of reproductive age, providing an option for long-term medical management of the condition. Long-term use of Esmya is usually well tolerated and typically given when surgery is not a preferred treatment.

Hysteroscopic morcellation of submucosal fibroids as an outpatient procedure

This procedure involves the excision of fibroids affecting the lining of the womb and are responsible for heavy bleeding or subfertility. Experienced and appropriately trained gynaecologists can remove fibroids by placing a telescope (hysteroscope) inside the womb and using a morcellator to cut away and remove the fibroid tissue. The procedure can be carried out under local anaesthetic in a clinic setting whilst you are awake and able to talk to the doctor or nurse.

The patients can go home immediately after the procedure.

Why should I have a fibroid removed under local anaesthetic?

• The procedure performed in a more familiar, friendly and less intimidating environment

• No need for general anaesthesia and the risks it involves

• Reduced number of visits and reduced cost

• Minimal time off work and immediate return to regular activities

• Reduced risk of infection and operative complications

Do I feel any pain during these outpatient procedures?

There may be some discomfort, but this is usually minor and feels like period pains. On a scale from 0 to 10, patients usually grade their pain/discomfort at around 1 to 2.

Before and after the procedure

On the day of your procedure you can eat and drink as normal. You will be encouraged to take some pain relief (Paracetamol or Ibuprofen) 60 minutes prior to the procedure.

A nurse will be with you during the course of your procedure.

Depending on the procedure, you may experience light bleeding or discharge for a few days. This is usually minor and won’t interfere with day to day activities.

You will be able to go to work next day. One study showed that over 97% of women who have had an outpatient hysteroscopic removal of fibroids (Myosure) are likely to recommend the procedure to a friend.

Hysterectomy

Some women, whose family is complete, or who are happy to remain childless, may elect to have a hysterectomy rather than try to save their uterus. A hysterectomy is often recommended for particularly large fibroids where the uterus is causing severe compression symptoms or causing notable distension of the lower abdomen. For some women, the time taken to recover from their surgery is much more important than whether or not they can conserve their uterus. Women with a very large fibroid mass will recover from a hysterectomy very much more quickly than a myomectomy. Other women are so fed up with the problems they have had managing their periods, often for many years that the added guarantee of no periods following a hysterectomy is more than welcome. Hysterectomy also has an advantage over embolisation because tissue is sent to the laboratory for histological examination.

There are risks of complications with hysterectomy, notably from bleeding or infection and also of damage to the bowel, bladder or ureters and possibly prolapse at a later date. The risk of damage is greater with a larger uterus because the anatomy is often distorted by the sheer size of the fibroids, particularly cervical fibroids. The risks are also greater in women who have had previous surgery, Caesarean sections and pelvic infection in the past. Provided your surgeon is alert to these possibilities and appropriately trained and experienced the risk of serious complication can be minimised.

Some surgeons choose to reduce these risks by performing a subtotal hysterectomy so that the pelvic floor supports are left intact and the bowel or bladder are not disturbed. Recently a modest number of surgeons have been performing laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy. Most women will be well enough to go home from hospital the day after a laparoscopic hysterectomy. Fig 6 shows the difference between a total and subtotal hysterectomy with or without ovarian conservation.

Laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy is a minimal access procedure performed using a 10mm telescope introduced through the navel. The upper part of the uterus, containing the fibroids is removed by a morcellator as with a laparoscopic myomectomy, so the tissue can be examined in the laboratory. The complications of this procedure are minimal and recovery is quick because very little damaged tissue is left behind.

This short video shows a laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy being performed.

--video5--

What about the ovaries?

A total abdominal hysterectomy means removal of the whole uterus, including the cervix and does not relate to the question of whether or not the ovaries are removed. The ovaries can almost always be conserved at hysterectomy, unless there is an unusually large fibroid close to the ovary, compromising its blood supply, or severe post-operative adhesions. In women of childbearing age who have elected for hysterectomy, or in the incredibly rare situation where we have been obliged to perform a hysterectomy due to bleeding in the course of a myomectomy, we will always try to conserve the ovaries.

In women who are menopausal, it is thought that the ovaries contribute very little to the hormone status, and removal will remove any risk of development of ovarian cancer. Therefore in the rare cases in which we perform hysterectomy for women their late 40’s or early 50’s we will usually discuss whether or not we should remove the ovaries. This is a very personal decision. Some women are very risk averse and have a dread of developing cancer, others have a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer and are at risk through inheritance of the BRCA-1 gene. It would obviously be sensible to remove the ovaries in such cases. Other women prefer to remain intact and we respect their wish to retain their ovaries.

Conclusion

Uterine fibroids are common and can cause a range of symptoms. Treatment should be individualised on the basis of the symptoms a thorough assessment with modern imaging techniques and careful consideration of your preferences and in particular your desire for a family.

Recent advances in gynaecology allow us to review, assess and even treat uterine fibroids in the clinic, without the need of multiple appointments and admission to the hospital.

Investigations as a transvaginal ultrasound (2D or 3D), hysterosonography and outpatient hysteroscopy can be performed in an office gynaecology setting and guide us towards the appropriate treatment.Submucosal fibroids have a huge impact on fertility outcomes and are mainly responsible for heavy periods. The outpatient removal of those fibroids with minimally invasive techniques should be explored and offered in appropriately selected patients.

For further information on the authors of this article, Consultant Gynaecologist, Mr Adrian Lower, please click here, to find out more about Consultant Gynaecologist Mr Pandelis Athanasias, please click here

The time of a woman’s life when her ovaries stop releasing an egg (ovum) on a monthly cycle, and her periods cease

Full medical glossary